Context:

There’s a real shift in how early-stage capital is deployed. Seed rounds used to be about testing ideas with a little optionality. Now, they’re $10–20M “seed” rounds before anyone knows what the product is. It’s not just founders taking the money, funds have gotten bigger and need to deploy more, so they’re pushing larger checks, solving for their own asset management needs, not what’s best for company-building.

You see it in AI: companies raising billions at “seed,” then raising again six months later, while no one can explain what they do. It’s not just anecdata; it’s a structural change.

All of this points to a deeper shift in venture that I think a lot of us feel but rarely name. To close this out, I want to zoom out from the anecdotes and market noise and get back to a more basic question: what early-stage capital is actually for — and what we lose when we forget that.

Takeaways

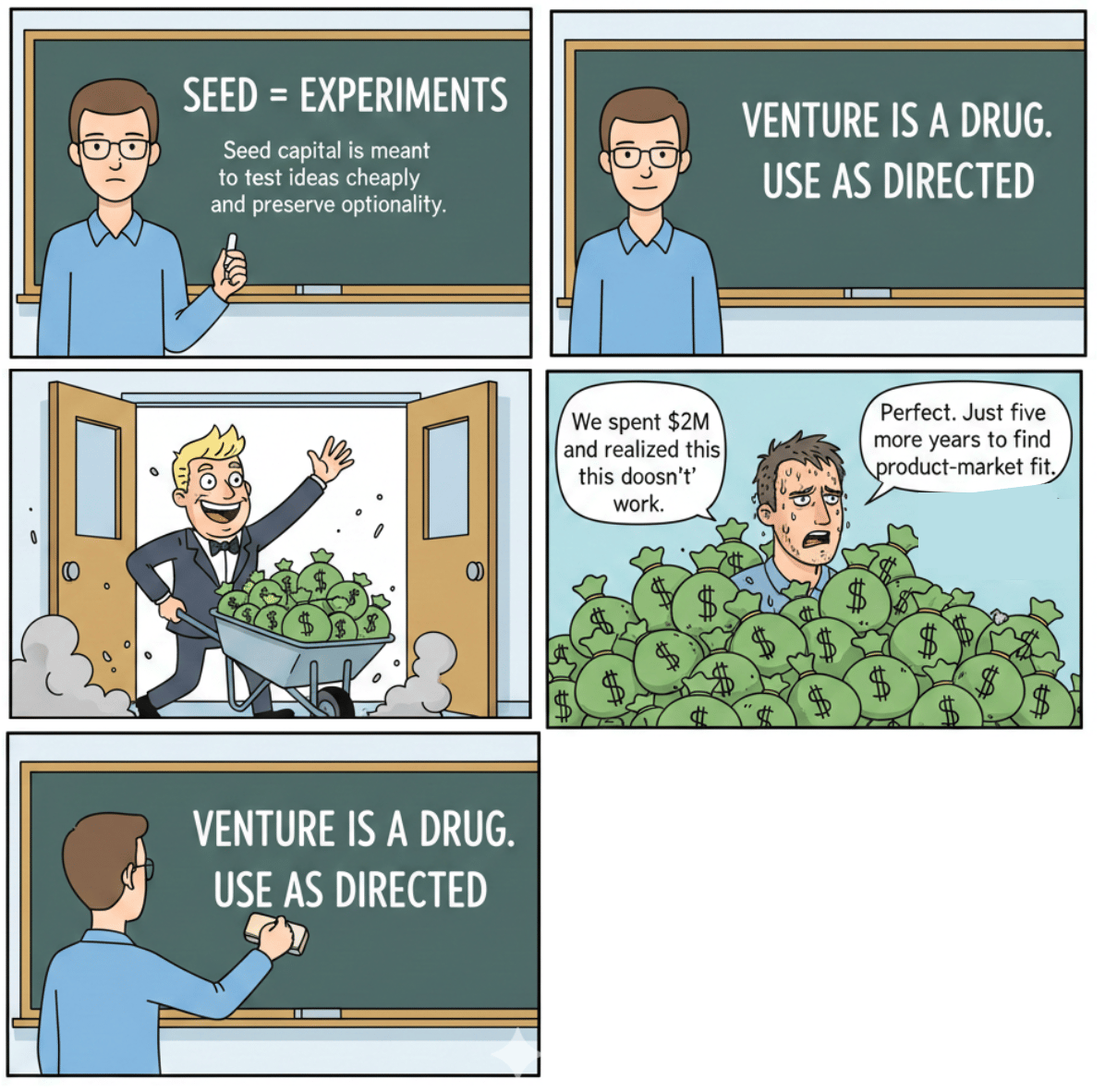

Overcapitalization kills optionality. If you take $10M and you’re wrong after $2M, you’re stuck with $8M—and five years of your life—when you should just admit you were wrong and move on. Taking too much too early traps founders and investors alike.

Seed used to be for experiments. The original revolution was AWS and cloud infra letting anyone start with a credit card and an idea. Now we’re back to massive data center buildouts, but with none of the discipline.

Venture is solving for fund size, not founder needs. As my buddy Kent Goldman (Upside Partnership) put it, funds are “solving for their needs around check sizes and deployment,” not for building great companies. FOMO and asset management drive behavior, not conviction or creativity.

Returns still come from the weird stuff. Despite all the platformization and central casting, the best outcomes still start “off-platform”—illegible, non-consensus places, not mega-rounds at crazy markups.

Financial discipline is out of style. Too many folks don’t know how to read a P&L, let alone define gross margin. Eventually, everything comes back to public market math, but in the meantime, people are marking up nonsense and calling it innovation.

Optionality and “crazy but inevitable.” The best founders are still the ones who are a little “punk rock” but inevitable. The market is overwhelmed with “central casting” types, but the real returns come from the outliers who run experiments, not those who fit the mold.

At the end of the day, I still believe venture capital is a drug and should only be used as directed. Early-stage investing only works when it preserves the ability to be wrong. The moment capital removes that option, it stops being fuel for creativity and starts becoming a constraint. The best companies I’ve seen still come from people running honest experiments, not from perfectly capitalized narratives.